USA – Today, the numbers have changed, at least in the western states. Now, the majority of crashes are out in the country, and motorcyclists are more often at fault.

USA – Today, the numbers have changed, at least in the western states. Now, the majority of crashes are out in the country, and motorcyclists are more often at fault.

Typically, a motorcyclist either does something dumb, or can’t control the motorcycle, and crashes into something.

One scary scenario is with the motorcyclist going wide in a right-hand curve and colliding with an oncoming vehicle. An example of this occurred on the Olym pic Peninsula northwest of Seattle, where a novice rider was out with some friends on a group ride.

According to newspaper reports, “…the motorcycle failed to negotiate a right curve. The motorcycle crossed the centerline and struck the right-front bumper of a southbound pickup truck that was towing a boat trailer. The rider was pronounced dead at the scene by a deputy coroner…”

This isn’t an isolated incident. There have been a huge number of motorcycle crashes where the rider crossed the centerline. You might wonder why. Some crashes near Friction Zone offices have Editor Amy Holland steaming. “I personally do not see any reason to cross the double yellow: not because it’s illegal, but because it’s just the right thing to do. The curves up here are all fairly easy. I have ridden on some hairy roads, and these don’t even come close. If you’re not paying attention, you can get tricked by a few of the curves, but if you can control your bike you can easily handle it.”

I agree with Amy that there is little to be gained by intentionally crossing the centerline, and potentially a lot to lose. The key here I think is “if you can control your bike.” I’ve seen lots of examples of riders who didn’t seem to have a clue about balancing and steering a two-wheeler.

If you observe other riders you’ll see all sorts of body English being applied, such as elbows or head leaned toward the curve, a knee against the tank, or boot-skids dragging on the ground. But the reality is that it’s steering the front wheel that causes the bike to lean, not the peripheral monkey-motion of flailing elbows, knees, or feet.

Unfortunately, today’s novice training courses don’t have a lot of time to cover the essentials, so steering control may be getting shortchanged. It may take a few months for a new rider to get the hang of balancing and steering a bike. There are even lots of experienced riders who aren’t very good at getting around curves.

Let’s go back to that Olympic Peninsula crash, and see if we can make sense of it. We’re not trying to place blame on anyone. Rather we’re trying to learn from a tragedy. Entering a right-hander the bike suddenly straightens up and not only crosses the centerline but hits the right front corner of the oncoming truck.

This can’t be simply a matter of misjudging the corner. The motorcycle didn’t just veer a little wider; it lifted up and went straight—all the way across both lanes. In my opinion, the most reasonable explanation is that the rider panicked and steered the wrong way.

Here’s how that might happen: a novice rider suddenly realizes the bike isn’t turning quickly enough toward the curve. Panicking, the rider steers the front wheel more toward the curve, as you would steer a car. But two-wheelers steer “backward.” That is, a bike leans (“rolls”) opposite the way you steer the front wheel.

To get the bike leaned over farther toward the right you need to momentarily steer the front wheel toward the left. If you steer the front wheel toward the right, the bike rolls left and straightens up, which is very likely what happened in the above crash.

A live example of this on YouTube:

Some riders understand that steering the handlebars controls lean, and consciously press on the grips to lean the bike. But apparently there are lots of riders who don’t really understand what it is they do to steer the bike. They just go riding and hope they figure it out before something bad happens. They may flail the handlebars left-right, attempting desperately to find a solution that points the bike in the intended direction, like that rider in the YouTube video. It’s important that you get this steering business straight, not the least of which is to stay on your own side of the centerline in curves.

Yes, how you position your weight on a bike helps make it steer. Some riders are proud that they can balance a bike “hands off.” Others like to hang their weight off the inside of the saddle in curves, like the roadracers do. The popular term for using body position to steer the bike is “body steering.” If you think its body steering alone that leans the bike, here’s a little experiment to help you re-evaluate what’s happening.

Go out and sit on your bike, grasping both grips. Now, lean your torso toward the left. It’s very likely you’ll be pulling both grips to the left as you lean. And if you hang off toward the right, it’s almost impossible to not pull both grips toward the right. It doesn’t take much movement of the handlebars to initiate the lean.

So, whether you are aware of the steering input or not, shifting your body weight typically steers the front wheel away from the intended curve, helping roll the bike into a lean. The flip side is that shifting your weight back toward center steers the front wheel more toward the curve, helping straighten the bike up. What’s important here is to realize that steering the front wheel is the primary roll input.

Let’s note that two-wheelers are turned in two basic steps. First, the bike needs to be rolled toward the intended curve before it will turn. Second, the front wheel needs to be steered toward the curve to force the bike to turn.

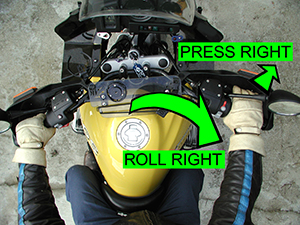

Diagram, bike rolled toward curve, Bike roll R

Diagram, bike rolled toward curve, Bike roll R

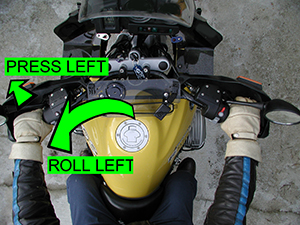

The first step in getting the bike to turn is getting it rolled toward the curve, which the rider can do by momentarily steering the front wheel away from the curve.

Diagram, bike turning, Roll R and turn

Once the bike is leaned toward the curve, the front wheel is pointed slightly toward the curve.

The common term for that initial press on the grips to get the bike rolled is called “countersteering” because the front wheel is momentarily turned opposite, or “counter” to the intended curve.

It’s only a momentary input, perhaps one or two seconds for a cruiser, or a half second for a sport bike.

There are some special steering situations that require more complex explanations, but for the moment let’s think of this simply as “push steering.” That is, push on the right grip to lean right; push on the left grip to lean left.

Veteran riders understand this intuitively. But if you haven’t been riding long, or if this whole thing confuses you, it’s time for another experiment. Take your bike out for a spin.

Find some vacant straight road or empty parking lot where you won’t scare the natives, and experiment with pressing on the grips.

At a steady speed of say 35 mph, relax your right elbow and give the left grip a little nudge. The bike will steer toward the left. Relax your left elbow and nudge the right grip. The bike will steer toward the right. All it takes is a brief press on the grip to steer the bike in that direction.

Pressing on the right grip will roll the bike toward the right. Pressing on the left grip will roll the bike toward the left.

Pressing harder on the grip will cause the bike to roll and turn more quickly. Holding the press longer will cause the bike to roll over farther. If it’s not obvious, you have to ease up on the press to keep the bike from steering to quickly or too far. When entering a turn, press on the grip until the bike is leaned about right, then ease up and allow the front wheel to steer toward the curve. The point of all this is to gain some confidence that pressing on the grips causes the bike to lean.

Top view handlebars, Push Right lean Right

Top view handlebars, Push Left lean Left

Pressing on the grips is what we all do to steer a bike, whether consciously or subconsciously. But once you are aware of what you actually do to balance and steer, you have the tools to put your bike exactly where you want it to go. If you find yourself in a tight turn and the bike is drifting too wide, press more aggressively on that low grip to tighten your line.

If you’d like more information on the subject, consider my book Proficient Motorcycling, second edition. And if you already know this stuff, make a point of passing this article along to novice riders who are still dragging their bootskids around, or wobbling over the line.

David L. Hough

The pedestrians coinmg from the right while making a right turn bugs the hell out of me. I almost hit a woman one time cause she walked out in front of the car while I was making the right turn. Even though this would have been my fault, as a walker/jogger, you should really make eye contact with the driver. If you don’t have that eye contact don’t assume.

Don’t try this at home but a short video and there are lots out there showing – counter steering – natural steering.

I have over 35 years experience in teaching people to ride motorcycles and have found that too many people over complicate or fail to understand why novice riders have problems with steering.

Trying to explain counter steering often leads to confusion and most people even instructors do not or have difficulty in understanding the dynamics of steering a motorcycle.

The reason novices (and some experienced riders) understeer (go wide) up to or over the centre lines is purely down to just a few initial mistakes.

How to correct the mistakes is the bit which takes a bit of practice and guidance.

Novices go wide because they get nervous and sort of panic, the reason is they tend to look at the opposite side of the road or centre line to see how near they are to it, also they may be or think they are travelling too fast. The problem then is that they are not looking where they are going.

The result is they go in the direction they are looking at (we call it target fixation). Because they are then starting to go wide they invariably try to lean the bike, unfortunately this then causes the bike to go in a straight line as the rider is by now not pulling the bars round.

The remedy to this problem is very simple but takes a bit of time for the novice to feel confident in doing it.

What needs to be taught to the novice is firstly where ever you look is where you will go to, therefore if you look in to the correct place you will go to the correct place. To steer the bike to the correct place you need to push vertically down on the appropriate side of the handle bars, in other words to go to the right you push vertically down on the right side of the bars. If the radius of the bend tightens up you just push down a bit more.

When explaining this to novices you must understand that most new riders do not understand how bike steering works and any previous two wheeled experience they may have had will have been on a pedal cycle.

The reason pushing vertically down on the bars for directions works is due usually to the fact that 99% of handle bar designs have the grip area swept back, this means that when you apply a downward pressure you will find that it is the bottom part of the palm of your hand which actually does the work and causes a momentary counter steering effect as it sort ot twitches the bars in the opposite direction, this then forces the steering over on to the edge of the front tyre.

A primary fact involved with steering a motorcycle is that the leaning in a corner is a direct result of a steering input on the handlebars to counter the centripetel (centrifugal) effect created when changing direction from a straight line. The steering geometry is designed in a way which creates a cone shape using the steering stem acting as a centerline making the bike lean into a turn.

I have used this method for 35 years and have taught well over 18000 and had an involvement with training over 30000 new riders as I do the job professionally in the United Kingdom for a living.

Ian Lee