United Kingdom – The history of motorcycle (and other vehicle) crime.

United Kingdom – The history of motorcycle (and other vehicle) crime.

Crime has been with us forever. The motor vehicle however has only been with us in one form or another since the late 19th century.

Like night follows day, vehicle crime followed up close behind & some offences are not quite as new as you might think!

In 1891 for instance the police force, already 60 years in existence, were aware of the disquiet caused by these ‘new fangled’ horseless carriages, and over responding to local pressures from a frightened public (not to mention the horses), they attempted to ban them from what could arguably be called roads.

The ‘contraption’ owners however, who could list amongst them Lords, judges, wealthy industrialists and landowners, not to mention a few Chief Constables, were thankfully able to influence the Highways Act 1895, which at least allowed them to keep and use there vehicles, providing a 14 miles per hour speed restriction was observed.

Both cars and (motor)bikes, now fitted with pneumatic tyres were also released from the red flag requirement imposed on it since 1865.

By 1904 the speed limit had been increased from 12 mph to 20 mph for both the 17,000 bikes & cars now registered for the road.

The Automobile club had been formed in1897 and the 1903 Motor Car Act required vehicle owners to register their cars and motorcycles with the local council for twenty shillings (£1) and also obtain a licence from a post office for five shillings (25p).

The Automobile club had been formed in1897 and the 1903 Motor Car Act required vehicle owners to register their cars and motorcycles with the local council for twenty shillings (£1) and also obtain a licence from a post office for five shillings (25p).

An increase in reported vehicle crime as such was limited to abusers of the new speed limit, usually the ‘offspring’ of the vehicle owners.

These privileged few were no doubt trying to emulate the drivers in the Gordon Bennett races (the Jensen Buttons of that period) who were exceeding 40 miles per hour on their journey from one capital city to another.

The ‘borrowing’ of cars and motorcycles however, with or without permission for “joyous purposes”, as one Kent magistrate suggested, “was inappropriate, foolhardy and worrying for the owner”.

TWOCing (Taking Without the Consent of the Owner) or Joy riding began in 1903. Its 107 years old!

By 1904 nearly 29,000 owners had sought registration for their vehicles.

In Cheshire, just three years after compulsory registration, a new BAT machine had been ‘borrowed’ from the collection of vehicles owned by an eminent local surgeon.

The culprit, a young relative, had challenged his fellow students to a race, but had damaged his own P&M motorbike beyond repair.

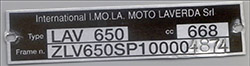

The registration plates (one letter and one number) from the students’ motorbike were placed onto the ‘borrowed’ machine and the race was run. The student won the race but was indiscreet and the owner took him to court.

The magistrate, a horse owner, likened the offence to the ‘Ringing’ of a horse and imposed a fine of 7 shillings. (Ringing; substituting one racehorse for another).

The term ‘Ringer’ had moved from four legs to two wheels and it is a word that still blights the automobile world to this day. (Ringer – we now know as a Clone!)

In 1907, the Automobile Association (formed in 1905) ordered their patrol cyclists to warn motorists of oncoming police speed traps. In Reigate, an over enthusiastic AA cyclist waved down a speeding machine to inform the driver of a speed trap ahead. The alleged (printable) reply was similar to “We know mate, we are the Police!”

Not quite an attempt to pervert the cause of Justice but interesting all the same.

Not quite an attempt to pervert the cause of Justice but interesting all the same.

Another disastrous attempt to catch speeding drivers occurred near Oxford when a photographer was summoned by the police to photograph the speeding vehicles complete with registration plate.

One motorcycle rider, startled by the flash, lost control, veered off the road and demolished the camera, covertly hidden behind a bush.

The photographer, who I am pleased to say escaped injury, might well have been involved in the very first Speed Camera.

Stolen or borrowed vehicles had not been publicly declared a problem in 1910. Some car manufacturers however had started to fit key operated locks to their door and ignition systems.

By 1914, certain garages were using mechanical pumps to distribute petrol. Previously sold in cans, the new pumps allowed this ‘expensive’ fuel to be sent directly from the pump to the vehicles tank.

In Lancashire, vehicles entering a certain garage triggered a bell by driving over a mechanical cable.

The proprietor, probably thinking that he had not had a customer for a while, found his severed cable hanging over a lamp standard in his forecourt and 5 gallons of fuel had been taken.

Not the first theft of petrol I am sure, but an early example of a ‘Drive Off’ without paying certainly.

In 1918, the First World War had ended and the total number of vehicles reported stolen to the Police in the UK was surprisingly less than 1,179 with London receiving just 211 vehicle crime related reports.

Up to then and certainly in the ‘sticks’ (countryside), it was quite common to notify the Chief Constable or his deputy personally of any vehicle theft and it was quite normal for him to have details printed onto posters which would be displayed in prominent places in the surrounding area.

This presupposes that most vehicle owners at that time were still fairly wealthy and therefore deserved the best treatment and advice the police could offer.

The cheapest car models available at this time were around £175, a whole two year’s wages to the average person.

Motorcycles were much cheaper however and much more affordable to the working man.

Motorcycles were much cheaper however and much more affordable to the working man.

The 1920 Road Act required all 591,000 owners to register their vehicles at the time of licensing, each one being issued with its own individual number.

There were at this time quite a few old and well used ex first World War vehicles being made available to the public, albeit still at a price that many could not afford.

In an auction sale in Dalston, London machines were sold for as little as £4 each and a quantity of 30 ‘mixed motorcycles’ were purchased by a Mr Wellesley for just £35.

He could well have been the first second hand motorbike spares dealer in the UK

Three armed carriers and a sidecar outfit were also purchased by a gentleman from Waterloo who used them for collecting people from the railway station and taking them sightseeing around London.

He was not registered as an official cab driver but could well be responsible for starting the first mini cab business. Any passenger ‘bilking’ (defrauding) this owner would I assume be in for a big surprise.

Typical of that period, much of the vehicle theft was opportunist and people simply borrowed motor cycles and cars to see how they worked, or perhaps used them to get home from a night out.

One recently demobbed Captain living in Victoria got fed up when his motor cycle was taken from outside his home.

He always removed most of the fuel from the tank before leaving it (lot of petrol theft then!) and on this occasion was fortunate to have found the machine by himself parked less than a mile away.

He recovered it and not willing to be a victim a second time he attached a flare grenade to the machine and connected the pin via string to the railings outside his house.

The wind unfortunately blew the bike over in the night and the explosion rendered the bike and his car parked nearby useless.

He was forced to pay for the damage to the windows in the neighbouring property, the railings and the shrubbery. He may well however have invented the first alarm and immobiliser.

In 1921 the first growing signs of car crime were appearing. The Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police reported the following.

In 1921 the first growing signs of car crime were appearing. The Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police reported the following.

“Amongst other crimes, larcenies of motor vehicles have been frequent. These, again, are in a large measure due to the carelessness of owners”.

With no door or ignition locks, alarms, immobilisers it is difficult to understand how a driver could be careless.

It is known that in this the first serious mention of vehicle theft by a senior police officer, several well known persons had earlier reported their vehicles stolen clearly using the publicity to their advantage.

Several were in reality just misplaced due to the owner’s alcoholic amnesia.

In those days, vehicle insurance existed but was not readily available or indeed considered by the majority of owners.

When a Mr Swaby of Dorset found his Rudge Multi missing, all of his estate workers and those from neighbouring farms went looking for it.

Together with the local constabulary, led by its superintendent, it must have been an impressive scene, likened only to that of a murder hunt or a film set.

With little petrol in the tank, the culprit, an army deserter, however was soon caught. Just as well, Mr Swaby’s insurance, a staggering 6 shillings per month covered nothing outside the curtilage of his house.

In 1926 1.7 million vehicles were registered for the roads in the UK.

Believe it or not, in 1928 the then Minister of transport passed an order making it illegal for drivers and riders in London to lock their cars, vans and motorbikes when parked in public places.

We can’t establish for sure the Minister’s mind set at this somewhat unusual law, but enquiries from ancient memories suggest that London was simply grid locked with vehicles and horses preventing the capital’s business men (and I assume M.Ps) getting to their places of work.

One assumes that if the vehicles were left unlocked, then the police could move them around easily should they become an obstruction.

When thefts of and from these unlocked vehicles, bordered on full blown looting, an early end to this regulation was agreed.

When thefts of and from these unlocked vehicles, bordered on full blown looting, an early end to this regulation was agreed.

Fingers were pointed at several organised London gangs who now operated in London and rumours ere that they had taken control of the theft and disposal of these stolen vehicles. Organised Vehicle Crime had arrived.

In 1929, in central London, a failed robbery at a jeweller’s shop forced the villains to flee. They pushed a rider from his machine, which happened to be stationary at some traffic lights (invented 2 years earlier) and when he bravely fought back, a gun was pointed at him.

He fled the scene but not before he had ‘locked’ the handbrake.

This might be the first manufacturer’s or after market Anti Theft Device ever (we are not sure) and it would be over 30 years before anything like it was made generally available to the public.

The two villains incidentally were eventually overpowered by passing draymen.

The judge at the inner London assizes, prior to sentencing the pair, had read about the recent Valentine’s Day massacre in America and the ‘Hijacking’ of illegal liquor.

He said “The offences, including the attempt to commandeer, expropriate, no – ‘hijack’ this vehicle with a gun, will be punished to the maximum extent that the law will allow”

This could well have been the first time ever a vehicle had reportedly been Hijacked.

Nearly 1 million vehicles of all types were on the UK roads by 1930 and with over 7,000 road deaths reported, third party insurance was at last made compulsory.

In 1932 the bazaar London Traffic (Parking Places) Regulations of 1928 were withdrawn and drivers were now encouraged to lock their vehicles.

In 1932 the bazaar London Traffic (Parking Places) Regulations of 1928 were withdrawn and drivers were now encouraged to lock their vehicles.

Also car manufacturers were now encouraged to design a standard device to prevent cars from being stolen.

The door lock had arrived and Crime Prevention advice had begun.

1934 was the year that the police decided to record theft statistics.

The vehicles on our roads amounted to 1.5 million yet only 1,303 incidents of theft were reported.

By 1939 at the outbreak of war there were nearly 2 million although many of these were ultimately either commandeered for war work or laid up for the duration.

With petrol heavily rationed (200 miles per vehicle per month) the ‘Black Market’ was working overtime. Motorcycles were very much in demand (more miles per gallon).

Music hall comedians joked that a soldier’s jeep or motor cycle may run dry, but you could still buy a gallon of petrol in the Fulham Road for a pound note.

In 1941 the war, petrol rationing, and a restriction on vehicle movements saw only 1 million vehicles of any sort on our roads, half of that two years earlier.

In 1941 the war, petrol rationing, and a restriction on vehicle movements saw only 1 million vehicles of any sort on our roads, half of that two years earlier.

This would all change however when the Second World War ended, bringing with it the most bizarre collection of surplus vehicles ever seen to these shores and affordable motoring for all.

1946 saw a staggering rise in theft in the UK to 5,171.

The potential profits had been scrutinised by the organised criminal gangs and vehicle crime was in its ascendance.

Vehicle crime peaked in the UK in 1993 when 592,660 vehicles were reported stolen including 115,000 motorcycles.

Today less than 200,000 vehicles are stolen annually including 30,000 motorcycles and scooters.

Dr Ken German

Really amazing.

A great article.

Thank you for share Ken.

I agree Ian, that would be interesting – e.g. we all know that HDs are the best bikes to ring because HDs have replaceable crank cases with ID numbers (Other makes do not). So – allegedly – all you need is a frame, new crank case and Bob’s your uncle – Fanny’s your aunt. Perhaps that’s why recovery rates for HDs is so low? Could Ken enlighten us?

Very interesting and informative, I hope Ken is going to do some more articles on things such as identifiying altered VIN details and engine numbers.

Great article. Makes motorcycle crime sound very interesting.

🙂